How I had a bygone 72-pin connector remade just to play Duck Hunt

I had been looking at component catalogs and distributor inventories for so long that my eyes were throbbing. I was searching for a particular circuit board connector, but it seemed there were none to be had. Not here, not there, not anywhere in the world. They no longer existed.

I realized I was down to a single option: a custom manufacturing order. I had never done that, and the prospect scared me.

Why bother? To play Duck Hunt, obviously.

The connector was — deep breath — a 72-pin straddle-mount female card-edge type, somewhat similar the expansion-board connectors on a computer motherboard. That alone would be, if not common, at least not too obscure, but there was a catch: I needed a 2.50 mm pin pitch, not the standard 2.54 mm pin pitch.

Thanks, Nintendo.

For reasons lost to history, Nintendo used that 2.50 mm pin pitch on their Nintendo Entertainment System (NES) game cartridges back in the 1980s. If there were just a few pins on a cartridge, the 40-micron difference between 2.50 and 2.54 mm wouldn’t really matter, but with so many pins, two rows of 36, the summed error is enough to cause shorts near the card ends.

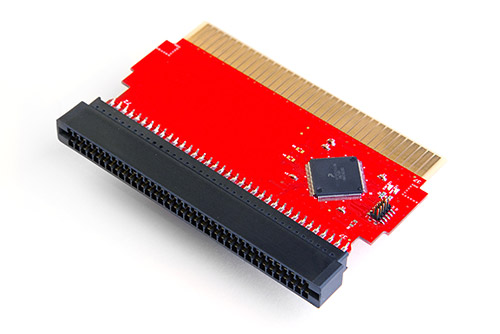

The motivation was a project of passion: getting the NES game Duck Hunt to work on an LCD TV. The game usually requires an old CRT (tube) TV, but I’d figured out how to modify it and the Zapper light gun to make it work on with an LCD. I needed the 72-pin connector to build a pass-through board that would apply certain patches to the game on the fly to let it tolerate things like extra video input lag. It would be conceptually similar to a Game Genie. In fact, my early prototypes of the pass-through patch board used a 72-pin connector salvaged from an old Game Genie, but that approach was a huge pain and required sourcing and destroying old Game Genies.

The connector as it will be used: on a pass-through board to patch Duck Hunt so it will work on modern TVs.

I began my search with the US-based suppliers, but when I started getting quotes above $7 per connector in low-thousands quantities — and that was just for standard 2.54 mm pin pitch — I realized that was untenable. Nobody would even return my calls when I attempted to clarify that I was looking for something non-standard, like 2.50 mm pitch.

While contemplating what to do, I happened upon a story at written by a guy in a similar situation a few years earlier. He had needed some DB-19 connectors, which were similarly no longer manufactured. He went to China, the “workshop of the world”, and so, I would go there to.

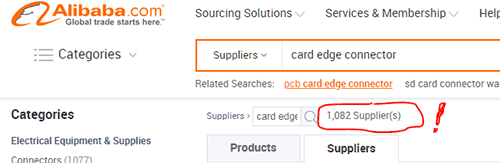

Alibaba had always fascinated me. It was a land of broken English but endless possibilities. Seemingly anything I could think of could be found there, either by the actual OEM or a factory that didn’t mind making a knock-off. The fact I’d never ordered anything off of Alibaba made it a little mysterious, but I was otherwise stuck, so I figured, “Eh, whatever,” entered “card edge connectors” in the box, and clicked “Search”.

Approximately 1,000 companies held themselves out as being potential providers. Hmm.

The trick, I learned, was weeding out the actual manufacturers from the mere distributors. In theory, that should be easy, since Alibaba allows companies to be categorized as “manufacturers” or as “traders”, but in practice, many traders also claimed to do a little manufacturing on the side, and vice-versa. In order to tell them apart, I had to look at their product lines.

If the company sold a wide variety of products across several categories, but claimed to have only relatively limited manufacturing floor space (also listed on Alibaba), that was a red flag. It was similarly a red flag if they used the same stock photos as everybody else, even if those photos were emblazoned with bespoke watermarks or graphical overlays.

After identifying six companies that appeared to actually make card-edge connectors, albeit with specifications different than I needed, I contacted them through Alibaba’s messaging system. I described what I was looking for and asked them whether they could provide such pieces and on what terms.

I also sent a technical drawing showing the 72-pin 2.50 mm pitch female straddle-mount cart-edge connector. I didn’t have one handy, so I grabbed a drawing for a 2.54 mm pitch connector that was otherwise appropriate, tweaked a bunch of things in Photoshop to match what I needed, and attached that to my inquiries.

Of the six companies, only three responded. The first sent a polite note that they could not help.

The second sent what has to be one of the gutsiest replies I’ve yet encountered in business. “Yes!” they said, they could sell me those connectors. In fact, they had them in stock, and they could ship them immediately for US$1.10 each. That seemed very suspicious. I asked them to send me a technical drawing of the part they had in stock so that I could check that it would meet my needs.

What did they send me? Why, a cropped version of the drawing I had sent to them!

I couldn’t believe it. It was definitely the crappy Photoshopped drawing I had put together, except with the edges cropped in. I was so surprised that I wasn’t sure whether to laugh or be angry.

The third company, one based in Guangzhou, was much more professional. After working through some clarification — yes, I was sure I wanted 2.50 mm pitch, not 2.54 mm pitch — they sent me a technical drawing of a connector they could produce. More importantly, it wasn’t the drawing I had sent in the first place. It looked perfect.

And the price? An order of magnitude cheaper than the non-custom connector the stateside manufacturer was trying to sell me. The only catch was that I would need to order 2000 of them at a minimum.

My fears rapidly shifted towards how to pay them and how they would get the components to me.

How did international payments work? How did shipping work? Would I need a broker? A fixer? A smuggler? I read horror stories about how payments to mainland China banks were tricky, how shipment was its own beast, replete with a sea of incoterms, and so on. Would I have to worry about customs? How would I even find out?

Fortunately, the connector manufacturer was large enough to have well-oiled solutions for such situations. I paid them via credit card using PayPal, the destination apparently being an account at a bank in Hong Kong. Then, for getting the parts back to me, they gave me a variety of EXW options, including DHL and FedEx. I chose FedEx IE, which balanced cost with speed.

The PayPal payment complete, I crossed my fingers and waited.

A few weeks later, but five business days ahead of schedule, I received a FedEx tracking number from the company. Woo! I was excited! Surely my connectors would arrive in short order!

Ha. Um, no.

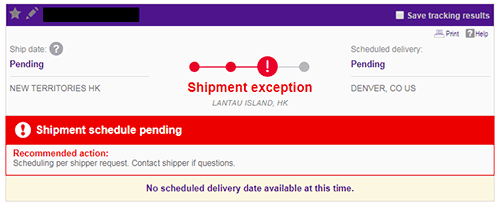

Thus began a 10-day slog in which I learned that FedEx IE (international economy) is a lot different than FedEx IP (international priority). An airplane was involved, but it might as well have been a slow boat.

I watched as my package lingered for days in Hong Kong. The FedEx tracking page claimed that the “shipping exception” was due to “scheduling due to shipper request”. It turns out that doesn’t mean my vendor requested something shipping-related, but rather, that FedEx itself was deprioritizing the package. Of course, none of that was obvious when I made the initial shipment, and getting more details about the shipping schedule beyond “It should arrive within a few weeks” was nigh-on impossible.

After the better part of a week, the packages started to move, albeit slowly and on an indirect route. Taipei. Anchorage. Memphis. Would it ever arrive?

But arrive the packages eventually did, on a sunny morning a month to the day after I’d first contacted the Chinese manufacturer. The doorbell rang, my dog Sophie barked, and there I found my 87 lbs. of connectors, all 2000 of them of them, boxed and covered in Hanzi characters. “Enjoy your… whatever they are!” the FedEx guy said.

I was giddy with anticipation as I cut through the tape on the topmost box. Inside, I found a stack of smaller white boxes, each labeled “72-pin female straddle 2.50mm” — a good sign!. I lifted the lid. There they were! My connectors, packed neatly in rows and layers.

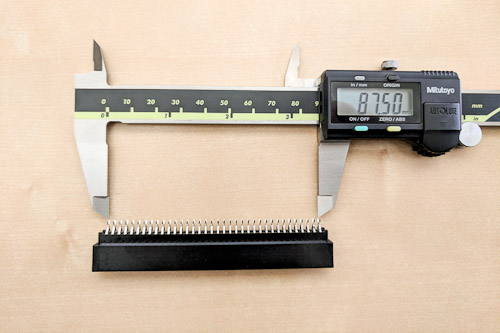

A quick check with calipers confirmed they were the correct size. Hooray!

Incredibly, they met specs: 36 pins (per row) at 2.50 mm spacing is 87.5 mm center to center from start to end.

I soldered one to the patch-board PCB I’d designed and plugged in a real NES cartridge. Worked great!

I zapped some ducks on my LCD TV to celebrate.

UPDATE June 28th, 2018: More to the story coming when I get around to writing it! In the meantime, I’ll jump ahead to the part where I made this available so you too can play Duck Hunt on your LCD TV.

I bow to your duck hunting persistence!

What? The entire story was just about the connector? I wanna hear about the chip you made..and what you did to create a tolerable lcd sync.

Also you could probably easily find a reseller for those connectors from project supply stores and console refurbish suppliers.

Nice project. Way to keep Duck Hunt supported for another generation!

@jeff Still writing that up. Coming soon!

That’s pretty darn cool.

I’m amazed you got this working without a LED bar or something similar, I honestly didn’t think it was possible to determine position accurately on modern TV’s.

The camera tells the difference between the white squares on the black screen, but how on earth did you solve the issue with multiple ducks on the screen?

Don’t know much about this, but on a TV that don’t draw lines in the same way as old CRT’s did, but just shows the image “at once”, wasn’t it hard to determine position?

How you actually did this, the technical stuff, would be interesting reading?

Is it the straddle mount that makes these connectors so hard to find, I believe I’ve seen the regular through hole mounted connectors in some catalogs not too long ago, but I realize those wouldn’t work inside a cartrigde.

Great work!

@Andrew

Thanks! The game displays one white square for each duck, with each square on its own video frame. Unlike other light guns, the NES Zapper doesn’t make use of the timing of the electron beam’s scan across the screen for determining position.

Still working on a more technical write-up. Trying to make it sufficiently detailed without being mind-numbingly dry. Hang in there for it!

The straddle mount is important for this application, but that’s not what makes these rare. The part that makes these so hard to find, and why I had to have them custom made, is the 2.50 mm pin pitch. The standard pitch, available from any major distributor, is 2.54 mm (0.100″). However, at the edges of the connector, the summed error of 0.04 mm times 36 (or 18, depending on your frame of reference) pin positions is enough that neighboring pins start overlapping and shorting out, since the wipers and the contact pads/fingers on the board are both quite wide.

Any chance on sharing the manufacturer you used? I’ve been digging into the possibility of having some custom connectors produced but choosing a manufacturer seems like a pretty daunting task. (as you have already found)