Formula 1000: How fast it does go

There is a deep-seated human drive to go fast. And when one experiences fast, invariably the target shifts towards going even faster.

“How fast does it go?” is the question I get from laypeople when they see my second race car, an F1000. Wings, a sleek body, an aggressive seating position — how could it be anything other than very fast? But the units they imply in their question — top speed in miles per hour — aren’t really the best way to judge such a machine.

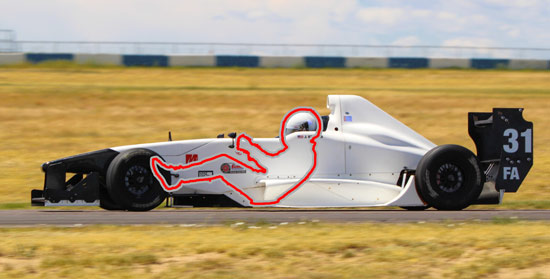

My second race car, a 2013 Phoenix F1K.12, during an SCCA race at High Plains Raceway in July 2020 (Photo: Rocky Mountain Pixels)

I quickly came to realize that I could give almost any answer, and that answer would be lost on them. The fact that they would even ask that question, phrased in that way, exposed their lack of knowledge about racing.

Racers don’t ask that question of one another. They will ask about lap times instead.

Yes, speeds enter the conversation occasionally, such as, “What was your minimum speed through turn 10?” However, to answer such a question, one must have a datalogger for post-session analysis. Even the rare few who have a speedometer visible on the track won’t be looking at it much. Braking, turning, and competitors dominate concentration already spread thin.

Moreover, the top speed is often misleading. Lots of high-horsepower cars can hit high top speeds on straights only to give the time back in the corners. If a car can hit 160 mph on the straight but needs to slow to 70 mph to make a turn, it will be worse off than a car that hits only 130 mph on the straight but can carry 105 mph through the same complex.

I prefer cars that can corner.

The Phoenix on its first night in my possession, in September 2019, sitting next to my Formula Vee (Photo: Sean)

When I started looking seriously for race cars in 2018, I quickly became enamored with a specific class: F1000. Wings! Big slicks! Paddle shifters! A 13500 RPM red line! Just 1000 lbs including the driver, and 190 hp from a bike engine!

The view with the engine cowling removed showing the 999cc 4-cylinder Suzuki K7 engine from a 2007 GSX-R1000 serving as its prime mover.

Friends told me I’d be in way over my head if I jumped directly to that from my beloved Boxster S. I’d be overwhelmed or perhaps even hurt myself, they said.

In hindsight, they were right, and I’m very glad I bought my Formula Vee in early 2019 as my first race car. I’m also very glad that I bought my second race car, a 2013 Phoenix F1000, eight months after that.

I bought it sight unseen, over the internet, based largely on the stellar reputation of the seller (who also built it). Still, I knew from even my limited experience that I was taking a bit of a risk, and not just in the obvious ways: there was a chance the car wouldn’t fit.

When people test a formula car for fit, they say that they are “trying the car on”. When you have the fit right, and you’re fully belted in, you feel as one with the machine. If it doesn’t fit, you’re somewhere between disadvantaged and completely screwed.

Luckily, the Phoenix fit me well to begin with, and once I got my fully custom seat poured, it became so comfortable that I could fall asleep in it. The key is that the seat was molded to my body using an esoteric SFI-rated two-part expanding foam, then covered with flame-retardant CarbonX fabric.

When it’s time to drive, I simply slide in and do up the six-point harness as tight as possible. The tighter the belts are, the more the car can communicate with me, and the easier the car is to drive. I like them so tight that I involuntarily exhale a bit as they’re being tightened.

In the cockpit back in the paddock after a race. Looks tight, but it’s actually super roomy by formula-car standards, and it’s extremely comfortable. (Photo: Sean)

In my seating position, my back is inclined about 45 degrees, and my feet and legs are above my butt. My butt, in turn, is about 1/4″ above 21 lbs of lead ballast (to reach the minimum weight), and is only about 1.75″ total above the ground when the car is at rest. That decreases to about 1.25″ when the car is at high speeds and the downforce is extreme.

Red outline shows my approximate position in the car

When you get the F1000 on the track, the acceleration, brakes, and glorious engine note are what you notice first, but what’s really mind-bending is the grip in the corners. You can turn in at what seem like impossible speeds, and yet the car holds. Better than that, it feels completely planted.

Some of that is due to the incredible Hoosier tires, which are as sticky as freshly chewed bubble gum when they’re at the proper temperature. A lot of it is also due to the incredibly stiff suspension, the fancy 4-way adjustable dampers at each corner, the low center of gravity, and the finely tuned setup of everything. All of that works in concert to produce staggering levels of mechanical grip.

But the part that really gets the heart pounding, and the part that takes a leap of faith mentally, is the aero package. The wings! The diffuser! And not to mention all of the critical but unsung trays, gurney flaps, and so on, that are critical to making everything actually work.

With the aero and mechanical grip combined, I see 2.5 G of sustained lateral acceleration in fast corners, with momentary higher peaks. By comparison, the very best production cars with aggressive street tires top out around 1.1 G (i.e., 1.1 times the acceleration due to Earth’s gravity).

The closest I’ve come to that sensation elsewhere is on very fast roller coasters, but there’s a difference: the cornering on the coaster makes sense, as it has steel rails. Trusting that the car would hold as if on rails was an enormous mental challenge. It took time and practice to reach that point.

So, is it fast? Oh yes. Almost incomprehensibly.

As mentioned earlier, the uninitiated ask about speeds, but drivers talk about lap times. Around my favorite local track, High Plains Raceway, the Phoenix is about 30 seconds per lap faster than my Vee, and my Vee is about 5 seconds per lap faster than my Boxster was. In a world where tenths of a second are considered significant, 30 seconds is an eternity.

That’s a testament to the design and execution of the Phoenix more than it is any particular level of skill on my part. The data suggests that the car easily has another few seconds in it.

Unfortunately, life is full of tradeoffs, and that speed comes at a cost.

The expensive part is operating it. If nothing breaks, the operating cost per lap is about ten times higher than what it is for the Vee.

And if the expensive part is operating it, the really expensive part is fixing it when it breaks, as it’s made from all sorts of exotic materials and bespoke mechanical pieces. “Carbon fiber” and “custom-machined” are its watchwords.

A bit of a mechanical problem meant the car got a ride back on on the hook after a race in August 2020 (Photo: Sean)

But when it’s working, the technology is a complete joy. Paddle shifters! Data loggers! Fuel injection! Limited-slip diff!

So, how fast is it? It’s fast enough to continue to challenge me in a pleasurable way, whether on the track, in the paddock, or at the shop. It’s fast enough to provide a thrill coming down the track wheel to wheel with another winged formula car, the two of us competing for position. It’s fast enough to spark conversations and relationships with interesting and, almost universally, wonderful people (much like in the Vee world).

Yes, as with the Vee, racing the F1000 is about the people and experiences. That’s the true core of the pursuit. The speed is fun, no doubt, and the machines are amazing, but at the end of the day they are means to an end. Machines do no good sitting in a garage, and the memories of a race weekend would be nothing without the people.

Recent Comments